Beneath a Wild Sky: Stories of America's Lost Birds

The idea for this show in the John and Peggy Maximus Gallery began when I was given a book chronicling the lives of extinct birds, Hope is the Thing with Feathers by Christopher Cokinos. The stories were poignant and shocking. I realized that an exhibit on the subject would be thought-provoking in the current sobering time of bird loss.

Because the exhibit space is devoted to antique natural history art, we could reveal the tragic histories of lost species through the work of Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon, who depicted America’s lost birds. It was a challenge to find the exact prints. After all, they were made more than 150 and in some cases 250 years ago: rare to begin with and not easily found. There were a few already in our collection but we needed several others.

Last spring we purchased a copy of Audubon’s lyrical portrait of the Passenger Pigeon, an important image in the exhibition. Just a week before the show was due to open, I received notice that a copy of Catesby’s Ivory-billed Woodpecker had cropped up on a print-seller’s website in Tennessee. I’d been looking for one for months. It was shipped the next day and made it into the exhibition just in time.

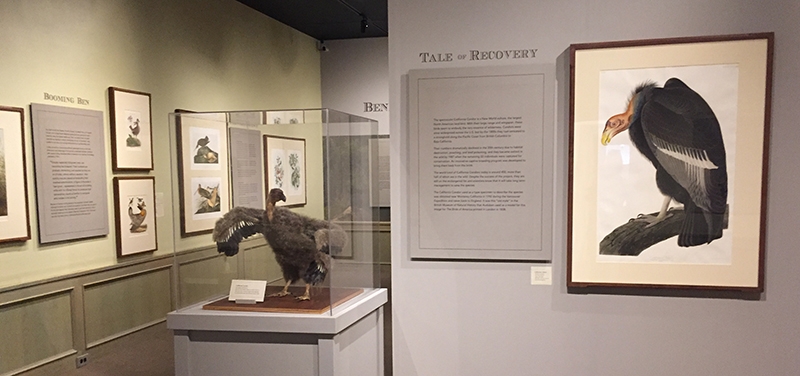

We also recently acquired and restored Audubon's great hulking portrait of the California Condor printed in London in 1838. Contrasted with the eight stories of America’s extinct birds is a tale of recovery about the California Condor.

Since its inception, the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History has been involved with efforts to save the California Condor. The Museum’s founder, William Leon Dawson, author of The Birds of California, pointed out the need to study the “noble bird…one of nature’s most majestic children” in 1923. Headed toward extinction in the 1980s, the last birds were brought in from the wild in 1987, to be bred in captivity and eventually released. The captive breeding program turned out to be surprisingly successful, and released condors are surviving in several areas of the West. Biologist and longtime Museum staff member Jan Hamber has been involved with the California Condor Recovery Program since the 1970s. Hamber began her field research on the endangered bird with naturalist and Museum Trustee Dick Smith. Trained at Cornell University, today she manages an archive of California Condor research and field observations that date back over 400 years. Hamber is passionate about seeing the condor returned to its historic range and still volunteers to track birds in the field.

Jan Hamber using a spotting scope to search for condors in Los Padres National Forest in 1983. Photo by Hank Hamber

We hope the images and stories from this exhibition might serve as a cautionary tale and inspire all of us to forge a more enlightened relationship with the nature around us.

I would like to thank Exhibit Designer Marian McKenzie for all her talent and hard work putting this exhibit together and collecting images for a digital version. It’s not the same as seeing the work in person, but we hope you enjoy it.

—Gallery Curator Linda Miller

What follows are images and text from the exhibit that opened February 7, 2020 in our John and Peggy Maximus Gallery.

Once an amazing diversity of birds, some in breathtaking abundance, inhabited the vast forests and plains of North America. But starting around 1600, species began to disappear as humans altered habitats, over-hunted, and introduced predators. The extinction of abundant species like the Great Auk, Passenger Pigeon, Heath Hen, and Carolina Parakeet took place within the past 150 years. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker along with Bachman’s Warbler and the Eskimo Curlew are also assumed gone.

Written accounts and images of these birds from first-hand observations were made by artists and naturalists working in early America—Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon. They witnessed changes within their lifetimes and, in words that were prophetic, speculated on what a future in a diminished wilderness might be like. The prints in this exhibit are original and made from their artists’ drawings in the 18th and 19th centuries.

“A century hence, they will not be there as I see them. Nature will have been robbed of many brilliant charms. The rivers will be tormented and turned from their primitive courses…the deer may exist nowhere, fish will no longer abound in the rivers, the eagle scarcely ever alight and the millions of lovely songsters be driven away or slain by man.”

—John James Audubon’s journal, December 1826

After Alexis de Tocqueville toured the United States in 1831, he concluded that its citizens were “insensible to the wonders of inanimate nature…their eyes are fixed upon another sight: The American people views its own march across these wilds, drying swamps, turning the course of rivers, peopling solitudes and subduing nature.” As Americans looked westward toward their “manifest destiny,” they considered divine providence as justification to “fill the earth and subdue it” and to “rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” The fish and fowl seemed limitless, the oak in the forests, infinite.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Englishman Mark Catesby devoted the first volume of his book on the natural history of Colonial America to birds. A hundred years later, Alexander Wilson, an émigré from Scotland, authored the eight-volume American Ornithology, for which he wrote the descriptions and drew and engraved the images.

John James Audubon came to America from France as a young man in 1807 and fell in love with its pristine wilderness. His pleasure was so great as he roamed the dense forests and painted birds that he wrote it was “as if the world had been made for me.” Yet each of these early artist/naturalists realized the idyllic wilderness they knew was beginning to change.

Once There Were Billions

Passenger Pigeon, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, London 1827-1838, hand-colored engraving

Passenger Pigeon, A Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Mark Catesby, Seligman edition, Nuremberg 1768-1776, hand-colored engraving

Passenger Pigeon, American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, Philadelphia 1808-1814, hand-colored engraving

When Europeans arrived in North America, it is estimated that 3–5 billion Passenger Pigeons populated the Eastern and Central United States. They were the most abundant land bird on the planet and traveled in massive flocks. Yet, because of unrelenting human exploitation for food and recreation, the wild birds were gone by 1900 and the last captive bird, nicknamed “Martha,” died in the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. The slaughter of these birds reached legendary proportions. No serious attempt was made to save the species until it was too late. The story of this bird is unique in human history and the lessons that it offers are critically important.

The most accurate firsthand accounts of Passenger Pigeons were written by preeminent artists and naturalists of the early 19th century. Alexander Wilson witnessed a flock passing overhead “of an almost inconceivable multitude.” For the first volume of his American Ornithology, he painted the Passenger Pigeon at life size, using the diagonal composition for maximum length.

Audubon wrote that in 1813 he observed a day-long flight of the migrating birds in Kentucky that obscured the light of the noonday sun as if there were an eclipse.

For this beautiful image from The Birds of America, he depicted a pair in a courtship ritual characteristic of members of the pigeon family. Ornithologists call this “billing,” in which one bird regurgitates food into the bill of the other.

Booming Ben

Pinnated Grouse, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, Bien edition, New York 1858-1860, gift of Wolcott Tuckerman, 1923, lithograph

Heath Hen, A Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Mark Catesby, Seligman edition, Nuremberg 1768-1776, hand-colored engraving

Heath Hen, American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, Philadelphia 1808-1814, hand-colored engraving

Like their cousin the Greater Prairie Chicken, the Heath Hen, or Pinnated Grouse, was a large North American game bird once common in early America along the Eastern Seaboard. Their courtship rituals included ostentatious displays in which a featherless air sac on the male’s neck swelled to the size of an orange while emitting a loud booming noise.

In the colonial era, these birds suffered catastrophic losses as the new Americans took advantage of the grouse’s predictable behavior patterns with wanton killing. Alexander Wilson observed in his American Ornithology published in 1810:

“Grouse, especially full-grown ones, are becoming less frequent. Their numbers are gradually diminishing; and assailed as they are on all sides, almost without cessation, their scarcity may be viewed as foreboding their eventual extermination. A figure of the male is here given…represented in the act of strutting while with his inflated throat he produces that extraordinary sound so familiar to everyone who resides in this vicinity.”

Because of intense hunting pressure, the population declined rapidly. Although the effort was ultimately unsuccessful, the Heath Hen was one of the first bird species that Americans tried to save from extinction. Only a few birds remained on the island of Martha’s Vineyard in 1927. Five years later, the last male survivor—nicknamed Booming Ben—was gone.

Presumed Extinct

Esqimaux Curlew, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, Bien edition, New York 1858-1860, gift of Wolcott Tuckerman, 1923, lithograph

Bachmann’s Warbler, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, Bien edition, New York 1858-1860, gift of Wolcott Tuckerman, 1923, lithograph

The Eskimo Curlew

This small wading bird had an elegant beak and a distinctive melodic call. Until the 1870s, these birds traveled in immense flocks making the arduous migration from Canada to New England, where they fattened up on blueberries and fruits before heading to South America for the winter. During stops on the long return north, they rested on the Great Plains where they fed on grasshoppers. Over time, as the West was settled and these prairies were converted to cornfields, the food source disappeared. Grassland birds like the Eskimo Curlew did, too.

These birds were relentlessly hunted for food and feathers through the 1800s until the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918 began to address the slaughter. But it was already too late. They were rarely seen after 1890.

John James Audubon painted this poignant pair in Labrador during his expedition to search for northern sea bird species in the summer of 1833. He depicted a dead female in a somewhat awkward pose in order to display the coloration of the underside of the wing.

Bachman’s Warbler

This warbler was named by Audubon for his close friend the Reverend John Bachman, who collected the first specimens. Its last known sightings were in 1988 in Louisiana. If not already extinct, this bird is listed as endangered and on the verge of extinction. It first fell victim to the millinery trade–its feathers were used in hats–and later to the draining of wet forest breeding habitats in the Southeast.

Even when it was more numerous, the shy Bachman’s Warbler was not easy to observe. Audubon never saw the bird alive and painted it from specimens in 1833 for Plate #185 in The Birds of America, hence the rather stiff profile poses of both male and female.

Pied Duck, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, London 1827-1838, hand-colored engraving, on loan from John and Bobbie Kinnear

Labrador Duck

The Labrador Duck dabbled for food in the shallows seeking small mollusks, shellfish, and seaweed with its large and especially adapted bill. “It procures its food by diving amidst the rolling surf over sand or mud bars,” wrote Audubon.

The species was never populous. Anything that can be said about the mating, nesting and breeding biology of the bird is conjecture based on inferences made from related sea ducks. In winter, the Labrador Duck foraged along the Atlantic Coast in sandy bays, estuaries, harbors and coastal salt marshes. Besides human predation, expanded settlement on the Atlantic Seaboard may have affected the food sources on which the ducks fed, as increased sewage effluent discharged into coastal shallows reduced shellfish numbers.

Historical sources agreed that the flesh of this duck tasted strongly of shellfish and it wasn’t popular to eat. Nevertheless, the Labrador Duck could be found for sale in Eastern city markets. But by 1870 it had vanished from market stalls. Over the next few years, not a single bird was sighted and ornithologists began to admit the possibility that the species was gone.

Audubon’s rendering of two Labrador (Pied) Ducks was painted in 1863 from specimens obtained from Daniel Webster.

Funk Rock

Great Auk, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, Bien edition, New York 1858-1860, lithograph

The Great Auk, a flightless seabird that once bred in colonies on rocky islands off North Atlantic coasts, has been extinct since 1844. The bird’s grim fate had been predicted as far back as 1785 by explorer George Cartwright.

“A boat came in from Funk Island laden with birds, chiefly penguins [Great Auks]. But it has been customary of late years, for several crews of men to live all summer on that island, for the sole purpose of killing birds for the sake of their feathers, the destruction which they have made is incredible. If a stop is not soon put to that practice, the whole breed will be diminished to almost nothing.”

A few traits made the Great Auk particularly vulnerable to extinction. It was totally unafraid of humans. Journal entries from early explorers describe how one could simply walk up to an auk and strangle it. The bird’s warm down feathers, which allowed it to swim in the cold North Atlantic, were in demand in Europe.

With its increasing rarity, specimens of the Great Auk and its eggs became collectible and highly prized by rich Europeans, which contributed to the demise of the species.

Fossil remains show that the Great Auk existed at least 500,000 years ago but became extinct within 300 years of first contact with European mariners. John James Audubon never saw a living Great Auk in nature. He drew this pair from specimens and skeletons in 1836.

King of Woodpeckers

Ivory-billed Woodpecker, A Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Mark Catesby, Seligman edition, Nuremberg 1768-1776, hand-colored engraving

Ivory-billed Woodpecker, American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, Philadelphia 1808-1814, hand-colored engraving

The largest woodpecker in North America, the Ivory-billed must have been an astonishing sight. One early naturalist wrote that he felt “tremendously impressed by the majestic and wild personality of this bird…its almost frantic aliveness.” They inhabited the swamps and low-lying riparian woodlands within the vast forests that stretched across the Deep South.

Alexander Wilson captured an Ivory-billed in North Carolina where he took it to his rooms to draw. The unhappy bird chewed through the furniture in its desperate attempts to escape. Finally, it refused food and died after three days. In executing the drawing shown here, Wilson suffered several severe cuts.

John James Audubon drew this trio of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers for Plate #66 of The Birds of America in Louisiana in 1863. He described the bird in great detail: its impressive appearance, behavior, and loud plaintive call. In Audubon’s era, these woodpeckers were harvested for their beauty. He noted that Native American chiefs wore regalia ornamented with the tufts and bills of the species.

The woodpecker’s preferred habitat was old-growth forests, and when they vanished, so too did the Ivory-billed, although some birders and ornithologists cling to the prospect that survivors might yet be discovered. Despite reports that they had been seen in the 1930s and more recent attempts made to film and record their sounds, no definitive evidence of a surviving Ivory-billed was found. It was left to Catesby, Wilson, and Audubon to provide us with firsthand imagery of these magnificent birds.

Beneath a Wild Sky

Carolina Parakeet, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, Bien edition, New York 1858-1860, gift of Wolcott Tuckerman, 1923, lithograph

Carolina Parakeet, A Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Mark Catesby, Seligman edition, Nurenberg 1768-1776, on loan from Bill Logan, hand-colored engraving

Carolina Parakeet, American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, Philadelphia 1808-1814, hand-colored engraving

Imagine a landscape filled with towering chestnut trees, great expanses of river cane, wolves, elk, panthers, and buffalo. Only 300 years ago, this vast wilderness was also home to large flocks of Carolina Parakeets, so named and described by colonial naturalist Mark Catesby in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, the first natural history of American flora and fauna.

The only parrot species native to the Southeastern United States, the Carolina Parakeet was bright green with a vivid reddish-orange and yellow head. The colorful noisy native birds ranged throughout the Eastern United States and extended into the West along river corridors.

Alexander Wilson wrote about a pet he named Poll and kept wrapped in a silk handkerchief during his travels. This was the bird he drew for his American Ornithology.

John James Audubon painted a group of Carolina Parakeets feeding on cockleburs:

“Our parakeets are very rapidly diminishing in number, and in some districts, where twenty-five years ago they were plentiful, scarcely any are now to be seen.... I should think that along the Mississippi there is not now half the number that existed fifteen years ago.”

—The Ornithological Biography, 1840-1844

Carolina Parakeets were still fairly common until the mid-1800s, when their diminishing numbers became apparent. The most tragic aspect of the parakeet’s extinction is that its decline was widely noted for decades. No evidence suggests that attempts were made to save the species. The last bird in captivity died in 1918 in the Cincinnati Zoo.

Tale of Recovery

Californian Vulture, The Birds of America, John James Audubon, London 1827-1838, gift of Mrs. Edward R. Valentine, hand-colored engraving

The spectacular California Condor is a New World vulture, the largest North American land bird. With their large range and wingspan, these birds seem to embody the very essence of wilderness. Condors were once widespread across the U.S. but by the 1800s they had retreated to a stronghold along the Pacific Coast from British Columbia to Baja California.

Their numbers dramatically declined in the 20th century due to habitat destruction, poaching, and lead poisoning, and they became extinct in the wild by 1987 when the remaining 22 individuals were captured for conservation. An innovative captive breeding program was developed to bring them back from the brink.

The world total of California Condors today is around 400, more than half of which are in the wild. Despite the success of the project, they are still on the endangered list and scientists know that it will take long-term management to save the species.

The California Condor used as a type specimen to describe the species was obtained near Monterey, California in 1792 during the Vancouver Expedition and taken back to England. It was this “old male” in the British Museum of Natural History that Audubon used as a model for this image for The Birds of America printed in London in 1838.

Birds Are Vanishing

North American birds are in decline. More than one in four has disappeared in the last 50 years. The story of the last Passenger Pigeon and the disappearance of the Great Auk, Carolina Parakeet, and Heath Hen reveal the fragile connections between species and their environment. As global reports paint a grave picture for the health of the planet, a new study finds steep, long-term losses among hundreds of species of birds from coast to coast.

The Passenger Pigeon vanished more than a century ago. We know now that extinction can happen to widespread, abundant species, not just rare ones with limited ranges. Increased protections and governmental policies that support conservation are essential to their survival.

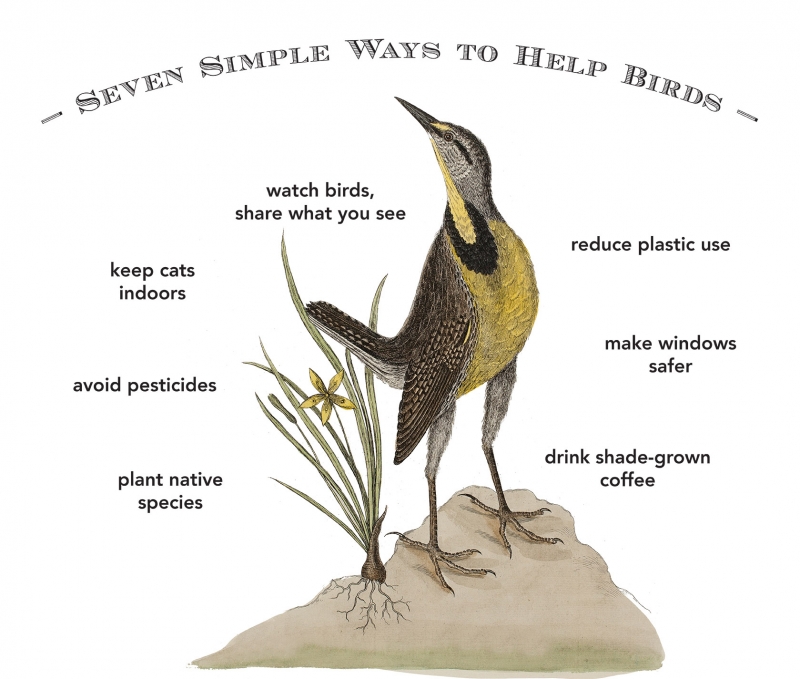

Individuals can also take action to protect birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology has advanced the data-driven choices listed below.

Painting at top of page: Landscape, Asher Brown Durand, Hudson River School 1861, courtesy of National Gallery of Art

3 Comments

Post a CommentA beautiful and sad, eye opener for those of us who are not always aware. Our planet is changing and so many of these wondrous birds are not here any longer. Beneath a Wild Sky is thought provoking indeed!

This is beautiful art work of equally beautiful bird life, most of which unfortunately, is no longer with us. Very good exhibit online, thoughtful, insightful and thought provoking. Thank you.

Absolutely beautiful, can't wait to go see this exhibit.