Curating Thousands of “Moss Animals”: Staff Celebrate a Digital Milestone

An interview with Department of Invertebrate Zoology staff

Owen: Congratulations on digitizing thousands of bryozoans. What are they?

Curatorial Assistant Van Henderson: Next time you're at the beach, take a close look at the kelp washed up on the shore; that strange white calciferous crust is most likely a colony of bryozoans, also known as “moss animals.” Without proper magnification or prior knowledge, one could easily mistake them for some sort of algae or moss. Bryozoans are similar to coral in that they are colonial organisms.

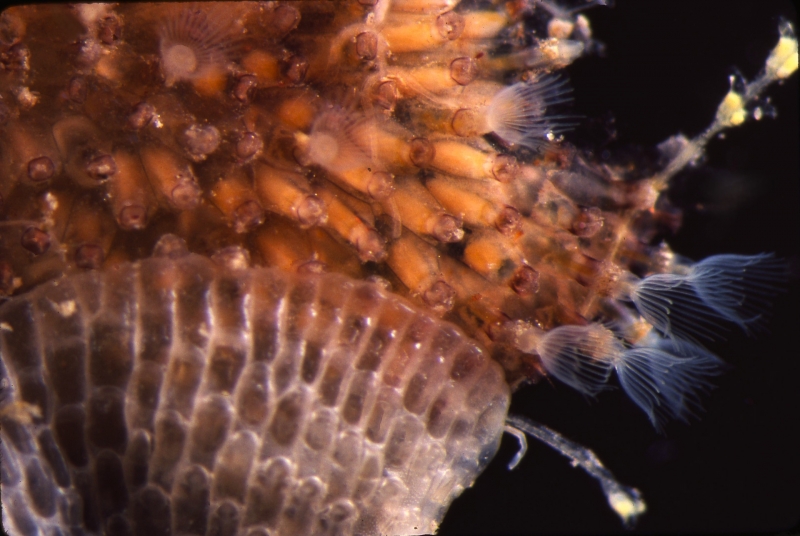

Kelp Lace bryozoans seen on the Wet Deck at the Sea Center

Curator of Malacology Daniel Geiger, Ph.D.: By looking at a bryozoan colony with a magnifying glass (or using the close-up function of your smartphone’s camera) you may be able to see the small boxes of the individual animals.

A microscopic view of this colony of Pherusella brevituba bryozoans shows individuals extending soft body parts from the skeleton to feed. Photo by Henry W. Chaney

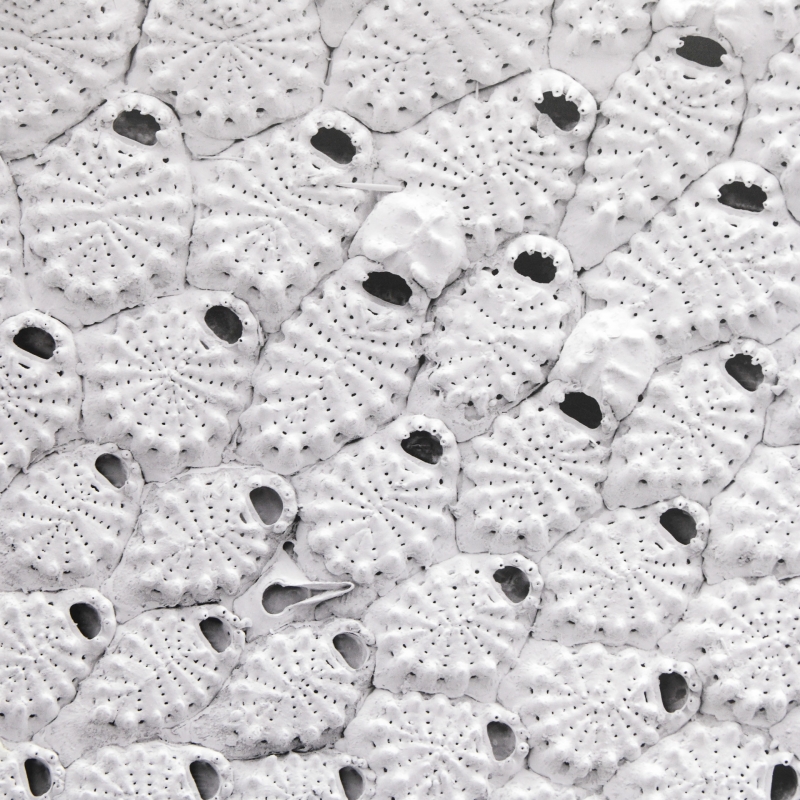

A scanning electron microscope reveals the skeletal structure of a cribilinid bryozoan specimen. Image by Henry W. Chaney

Daniel Geiger, continued: Kelp is just one place to find them: some bore into shells and other hard substrates. There are about 6,000–7,000 species worldwide, and most of them live in marine environments.

Owen: Why digitize our bryozoan specimens?

Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology Vanessa Delnavaz, M.A.: In the Department of Invertebrate Zoology, we're all continually adding to the long-term goal of cataloging all of our millions of specimens. Previously, only a small portion of our bryozoan collection was available online. We had a large collection of these understudied animals, but nobody could make use of it.

Thanks to a DigIn National Science Foundation (NSF) grant targeting everything but our shells, we’ve been supported to catalog and digitize many thousands of lots*, including almost 20,000 lots of bryozoans. Now, virtually all of our bryozoan collection is searchable by researchers and anyone who is interested all over the world.

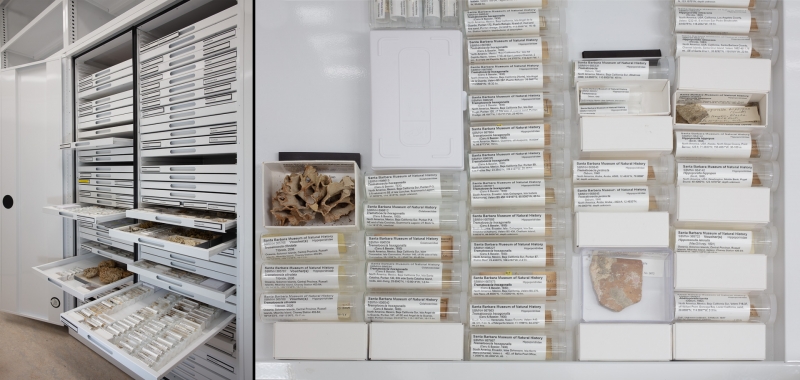

Different species in the collection illustrate a range of growth patterns.

Daniel Geiger: By cataloging our material, we also gain a better sense of what we have here.

As the principal investigator on this NSF grant, I had a wide range of responsibilities and problem-solving duties. One of those duties was to verify the status of type specimens—specimens designated as physical references when scientists describe a new species. They are critically important to science. During this project, we found the Museum holds over 1,000 bryozoan type lots. That's a very large number of specimens at that high level of scientific significance.

Bryozoan specimens are densely packed in our cabinets, but easy to find thanks to expert organization. Photos by Daniel Geiger

Daniel Geiger, continued: Because of the volume of material and work, we hired curatorial assistants under this grant: Alexandria Gour, Van Henderson, and Lucie Gimmel. I’m grateful to them for pushing through some of the really tedious parts of this project. I think it helped that I—as the senior staff member—led by example and assisted with the tedious tasks as well.

Henderson with dry specimens in the Invertebrate Zoology Collections

Iodictyum willeyi from Florida. This species stands out on the shelf: most dry specimens don’t preserve the colors of the living animals.

Owen: Can you describe some of those tedious tasks—in a way that’s not too tedious for the reader, of course?

Van Henderson: The hardest part of the project was the magnitude of the material. I would be lying if I said it wasn't occasionally demoralized looking at the once towering array of bryozoan boxes. Much of the information given in these slide boxes was vague, sometimes only offering three letters and a couple of numbers to describe the collection site, date, and collector. Thankfully, usually someone in IZ would be able to decipher the cryptic data. Most museums aren't equipped with the expertise we have in our department. Hank Chaney, the head of our Collections & Research Center, is a world-class authority on bryozoans, and I'd like to thank him for always encouraging my curiosity in these organisms. I'm proud of myself for learning the local intertidal species of bryozoans, so I was able to identify them to at least the family or genus level.

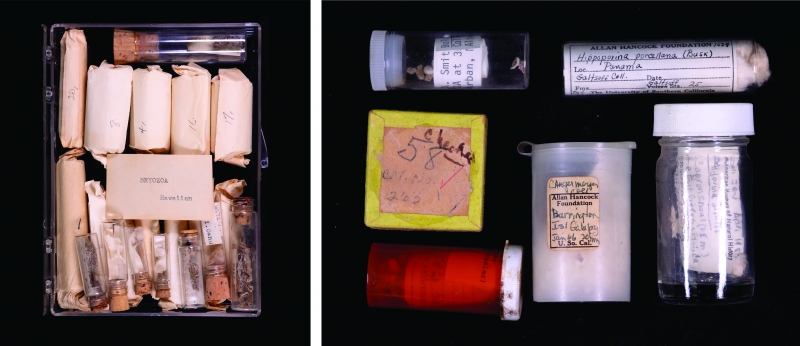

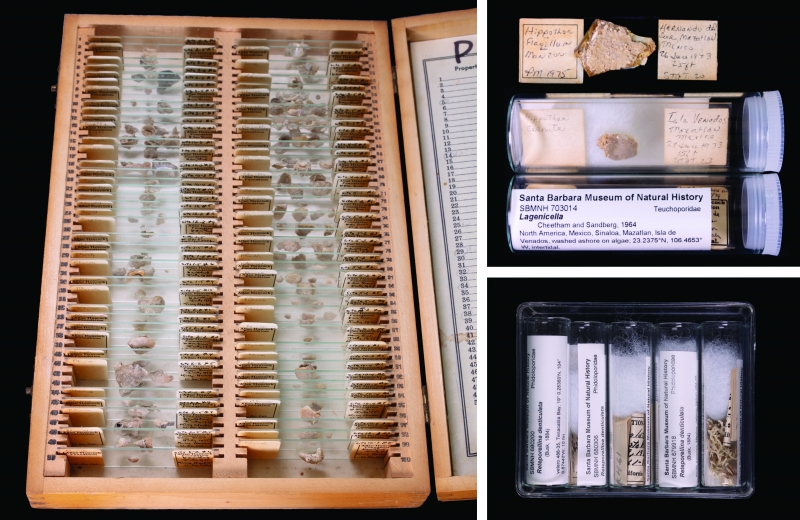

Specimens are donated to the Museum in a variety of containers. Many labels need decoding before the specimen can be digitized. Photos by Vanessa Delnavaz

Owen: After digitizing this huge volume of specimens, you extended your impact further by publishing about the project.

Daniel Geiger: Part of research is communication. If it is not published, it does not exist. So I took the lead on writing the article we’ve all recently published in Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals. It was an opportunity to show budding professionals like Van and Alexandria how scientific papers are written, and how the whole process works. However, our manuscript was accepted without any revision, which is extremely rare. In over 30 years of scientific publishing around 100 papers, this only happened to me once before.

Van Henderson: From my perspective, the Museum's objective is to not only preserve specimens and information but also to encourage curiosity and knowledge. Without publications such as ours, the niche but enthusiastic community of zoologists would be even more confined. With Bryozoa being such an understudied phylum, the more resources available on the matter, the better.

Curatorial Assistant Alexandria Gour: The accomplishment of digitizing such a high volume of material (I digitized about 2,000 lots!) makes our hard work worthwhile. For me, as for Van, the hardest part of the project was deciphering old labels and station data, and cross-referencing publications in search of the most correct data.

On a more physical level, I think that the published descriptions of how we are housing our collection will be extremely useful to museum professionals working with large collections of specimens (of any kind) mounted on histology slides. I’m proud of coming up with the idea of immobilizing histology slides using polyester batting when storing single slides in a capped vial, so they don’t rattle around.

Formerly in wooden boxes, we rehoused many old slides of bryozoan specimens into glass vials immobilized with polyester batting. This makes it easier to see the collection at a glance, and keeps specimens intact and separate. Photos by Vanessa Delnavaz

Vanessa Delnavaz: Our description of how we re-housed and curated specimens on glass slides will be of value to other museum workers. There's very little published on how to safely and efficiently store this kind of material.

Daniel Geiger: In terms of our other published findings, we also highlighted the importance of georeferencing specimens—determining the numerical latitude and longitude from a verbally described place name—right off the bat, at the time of data entry. Outsourcing this tedious process is currently in vogue, but we point out that such approaches are in fact counterproductive. It goes back to what Van noted about how someone here, who knows the context of our collections, is best equipped to decipher cryptic collection data.

Gour seeks clues to identify a tiny bryozoan specimen in the Invertebrate Zoology lab.

Owen: It's a lot to be proud of. Congratulations to you all.

Van Henderson: Thank you. I want to especially thank Daniel Geiger for spearheading this paper and doing much of the heavy lifting.

Daniel Geiger: I am grateful to Vanessa for taking on the role of communications liaison with the overall TCN grant, and ensuring that all the data generated was shared with larger data repositories.

Vanessa Delnavaz: I am proud of everyone in the department working together to complete this portion of the collection!

Daniel Geiger: It was long considered an impossible task...just too complex, too tedious. Now it's done, and Alexandria will soon embark on graduate studies in collections management at Oxford University. We provided on-the-job training, sent her to present at an international meeting for museum professionals, and with her own hard work she was accepted into all four programs for which she applied. Kudos!

* * *

Further reading: “How to Curate and Digitize Bryozoa: Experiences at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History,” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, 2024.

*In a museum collections context, a “lot” refers to one or more specimens collected at the same place and time. Many lots contain more than one specimen.

2 Comments

Post a CommentSo cool. Congratulations on digitizing so many bryozoans!

Very interesting post