Know Your Gorgonians—Or Else!

“I require my students to learn the names of things,” says Westmont Associate Prof. of Biology Beth Horvath, M.S. “Knowing who you share the planet with is part of your education. The name opens doors. It gives you access to information. That’s why I’m here at the Museum, and why my students get dragged here many times over the course of the year.”

In our Invertebrate Zoology Collections, Prof. Horvath invites her students to consider that “a lot of people think natural history museums are sort of passé and quaint, but no, absolutely not. There are questions that can only be answered by looking at the dead stuff. The dead can and do talk.” For many years, Horvath has carefully listened to what the specimens here in the Museum have to say about gorgonians, the little-studied organisms also known as sea fans.

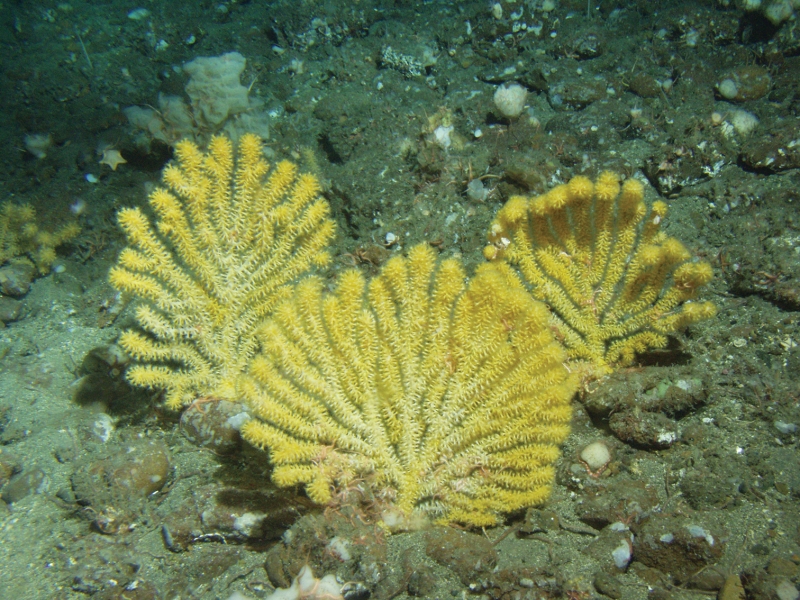

Often mistaken for plants, gorgonians are animals of the soft coral variety. Unlike their hard-coral cousins, they don’t build reefs, but are still capable of creating impressive structures. “When you see that sea fan, you’re not looking at a single individual,” Horvath explains. “It’s hundreds of thousands of these little sea-anemone-shaped creatures gathered together to form a structure.”

The flower-like yellow and white protrusions are individual polyps, the animals that make up the colonial structure of a sea fan. These were photographed in a kelp forest off the Channel Islands.

Growing perpendicular to the current, gorgonians filter plankton and detritus from the water to eat. Yet their role goes far beyond that of a passive receiver of food on an aquatic conveyor belt: they provide three-dimensional habitat in flat, relatively featureless ecosystems, like the wide, muddy plains of the deep sea. Within their barely-moving branches, other animals can reproduce, seek their next meal, or hide from predators.

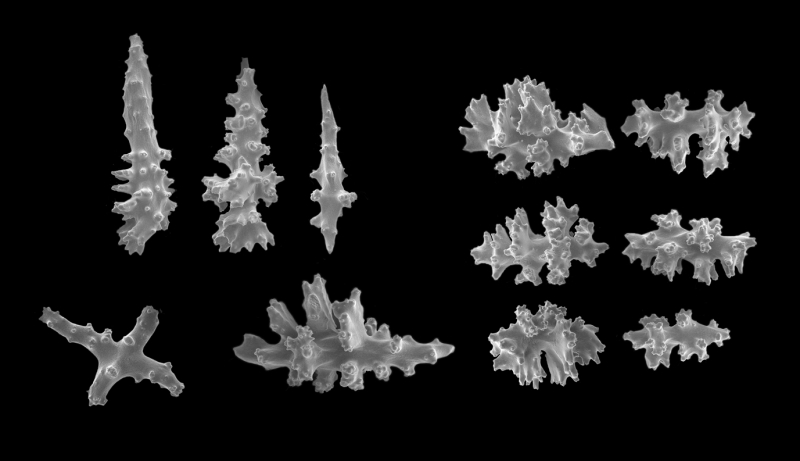

A gorgonian’s body has a firm internal axis that looks like a dead tree. Depending on the type of gorgonian, that axis is made up of either a complex protein known as gorgonin or tiny calcified hard parts known as sclerites. (The sclerites are also abundantly scattered throughout the soft tissues.) The tiny individuals—called polyps—secrete the axis and sclerites collectively. Over the organism’s lifetime, individual polyps are born and die, but the distinctive branching pattern that connects them endures. Undisturbed colonies have been known to live for 300 years.

Bright yellow gorgonians living deeper in the Santa Barbara Channel. Photo by D Schroeder courtesy of Milton Love

The shape, size, number, and arrangement of sclerites is partly genetic, but also influenced by environmental conditions like the current and temperature. “If it’s colder, they might build more sclerites, or they might be thicker,” says Horvath. “They’re very plastic. It makes them interesting.” To really know what species of gorgonian you’re looking at, you have to get extremely close, as Horvath often has, with the Museum’s scanning electron microscope (SEM). The SEM is a huge help in understanding how different sclerite shapes indicate individual species. “Sometimes you think you’re seeing the details under light microscopy, but then you look under the SEM and you see a lot more of the detail and the sculpturing.”

A range of sclerites from Swiftia kofoidi, as seen by our scanning electron microscope. Most of these are narrower than a human hair or a sheet of printer paper. SEM images by Daniel Geiger and Beth Horvath

“You have to figure out whether the differences point to a species, or whether the differences are just variation within a species.” Horvath has colleagues at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) who address the same questions by looking at genetics. As in many other subfields of biology, the two approaches—morphological and molecular—complement each other, filling in gaps, confirming findings, and pointing to new questions to investigate.

Horvath among the gorgonians in the SBMNH Department of Invertebrate Zoology’s wet collections (items preserved in alcohol)

Horvath didn’t set out to become the go-to gorgonian person, although she admits always being interested in nature. “I was the little girl in the neighborhood who brought home spiders and crickets and all that stuff.” She attended Santa Barbara High School, where she was inspired by her marine biology teacher, Louis Torres. She earned her master’s degree in marine science at Cal State Long Beach, and soon joined the faculty at Westmont in 1978, where she continues to teach field courses in marine science. Prior to focusing on gorgonians, she did everything from studying kelp forest monitoring videos to researching the discernment of hermit crabs (it turns out “they’re extremely picky about the kinds of shells they use”).

In spring of 2002, Horvath asked (now Emeritus) Curator of Malacology Eric Hochberg, Ph.D., if he had a project for her to do during a four-month sabbatical from Westmont. Dr. Hochberg pointed her to the gorgonians, an understudied group in the Museum collections. The Museum had just put out an impressive taxonomic atlas of marine species of the Santa Barbara Channel...but it left out gorgonians. Horvath took on the task of filling this gap.

Three weeks in, the scope suddenly jumped from a four-month interlude to a multi-year calling.

The University of Southern California started to disperse collections formerly held on Catalina Island, and Dr. Hochberg put in a request for the Museum to acquire all the cnidarians (animals from the wider group, including jellies, sea anemones, and corals, of which gorgonians are a part). Suddenly a long wall of boxes materialized in our invertebrate zoology lab: “There was a lot of gorgonian material in that collection, and it all had to be rebottled and identified,” Horvath recalls.

A selection of dried gorgonians from the Museum’s Invertebrate Zoology Collections. Clockwise from upper left: Leptogorgia chilensis (regularly seen in California, a little into Mexico), Eugorgia rubens (also very common locally, a little down into Mexico), Eugorgia daniana (southern end of CA Bight, well into Mexico), Pacifigorgia rutila (Mexico)

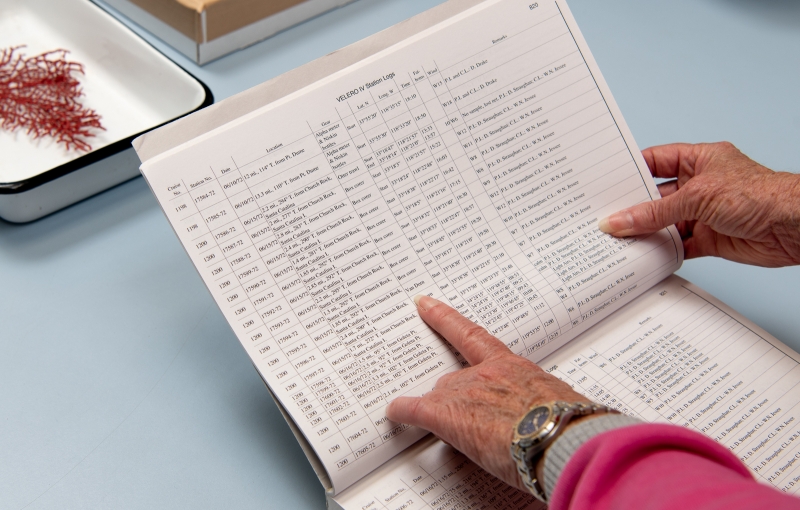

Over the next 14 years, Horvath studied the Museum’s entire collection of gorgonians from the Southern California Bight, the region stretching from Point Conception to Punta Colonet down in the north end of Baja California. Our collection includes some 515 lots* of gorgonian specimens, many of which were collected by the Alan Hancock Foundation Velero Expeditions of 1931–1941 and 1948–1985. The historic scope of the Velero specimens—accompanied by detailed records—provide an opportunity for researchers to understand twentieth-century marine biodiversity, and compare it with the present. But left alone, museum specimens and data only have latent potential. It’s hidden until someone like Horvath examines them and publishes her findings.

Detailed records from the Velero Expeditions show what make scientific samples uniquely valuable: they are well-documented snapshots of a specific time and place.

When Horvath shared her long-accumulated knowledge of our gorgonians in ZooKeys a few years ago, it was part of a dramatic expansion of the understanding of sea fans in our waters. “At the time that I started this, most people were under the impression that there were maybe 12, 15 species of gorgonian in the bight. Wrong.” Her publications—collectively the first comprehensive review of all the Southern California Bight’s soft corals—included detailed reports on over 40 species and 23 genera. “As NOAA runs deeper and deeper dive surveys, we’ll probably find more,” she says. “There’s a lot of real estate out there that hasn’t been looked at.”

Horvath’s work has enhanced the Museum’s collection and extended beyond it. She’s become a bicoastal gorgonian go-to person, consulting on the organisms for a wide variety of organizations, from NOAA, to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, to Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, to the Los Angeles County Sanitation District.

Contemplating her focus of study in the invertebrate zoology lab

The race to identify and understand gorgonians is up against two major threats: ocean acidification and human activities that directly disrupt the seafloor.

Like hard corals and shelled mollusks, gorgonians secrete calcium carbonate to build their structures. It’ll be increasingly harder to preserve that physical integrity as the environment acidifies. “We know that ocean acidification is affecting shallow-water farms,” where larval oysters struggle to survive. “Now we’re seeing those effects at greater depth,” says Horvath. “We thought we had more time before we would see those effects.” Water in the Southern California Bight has historically been more acidic than elsewhere, but it’s unknown how much acidity the animals here can handle. This is an active area of research.

Another cause for concern is deepwater trawling, a method of fishing that has long been called out for its counterproductive waste and destruction of habitat. When trawlers drag weighted nets across the seafloor, “it’s like strip-mining the bottom. You just wipe out an entire garden, as it were, of these corals. With that kind of fishing, you’re shooting yourself in the foot,” says Horvath. Nowadays, the economic interest in literally strip-mining the bottom for minerals, too, is a new worry for seafloor habitats.

Why should people care if acidic waters melt gorgonians, or if deep sea disturbances mow them down? Who will that affect?

If we can protect them, gorgonians may be a surprising source of boons for human health. Many cnidarians produce compounds of interest to medicine and are associated with helpful bacteria, so one fascinating area of research is their potential to help combat antibiotic-resistant infections, a critical public health issue. Their contributions to ecology are also an active area of research.

In graduate school, Horvath studied a tiny pelagic tunicate called Oikopleura—not a gorgonian, but still fondly remembered—“An interesting little bioluminescent creature. It makes this little mucous house around itself, and it filters phytoplankton. Those little mucous screens get clogged really fast, so they jettison the house and build a new one. You have all these little blobs of mucous floating around full of phytoplankton, which turns out to be a food source for juvenile commercial fish. It’s a very important link in the food chain.”

Unlikely ecosystem hero Oikopleura (not a gorgonian). Photo © CC. 2.0 Alexander Semenov

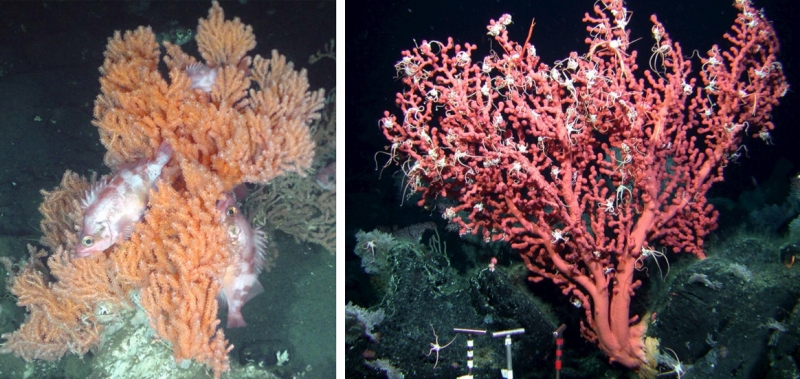

The study of ecology is full of such stories of overlooked benefit. And as noted above, the structures gorgonians create in otherwise flat habitats are clearly appreciated by many organisms. Biologists are studying the ecosystem services provided by cold-water corals, in particular how they serve commercial fisheries as fish nurseries, often with spillover from marine protected areas.

Deep-water gorgonians photographed for NOAA research in the Northeast Pacific: left, harboring rockfish, and right, spangled with stars

“I can’t tell you the number of pictures of deep-water gorgonians I’ve seen where they look like Christmas trees, hung with brittle stars,” says Horvath. “Worms curled around them, fish swimming in and out of them but never coming fully out of the colony, just sticking their heads out, looking around, and pulling themselves back in.”

Horvath keenly hopes her students will absorb the message that the ocean is more than a pretty surface. “There’s a lot going on out there. You need to know this stuff because ultimately your life depends on it,” she says. She has tough love for those who would prefer to be distracted. “The life that you lead terrestrially is dependent on whether or not those oceanic processes are functioning properly, and they’re really stressed out right now. Lots of people don’t like to hear that, but too bad.”

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: understanding taxonomy—being able to distinguish species—is the foundation of ecology and informed resource management. Like Horvath says, being able to recognize and name our fellow Earthlings opens doors to understanding them. Her decades of contributions—to the data in our collections, to published research, and to education—throw wide the gates to learning more about sea fans of the bight.

Further Reading

Elizabeth Anne Horvath, “A review of gorgonian coral species . . . held in the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History research collection,” ZooKeys 860, 2019. Published in three parts: Part I: Introduction, species of Scleraxonia and Holaxonia (Family Acanthogorgiidae); Part II: Species of Holaxonia, families Gorgoniidae and Plexauridae; Part III: Suborder Holaxonia continued, and suborder Calcaxonia.

*In a museum collections context, a “lot” refers to one or more specimens collected at the same place and time. Many lots contain more than one specimen.

8 Comments

Post a CommentGreat overview and phenomenal use of pictures! I am so glad to have had the opportunity to work with Beth and her important work get this feature! Thank you Owen!

Thank you so much for those kind words, Theo. It makes me smile to know that you're keeping up with your ol' colleagues here. For me, it was also a pleasure to work with Beth, and I hope this story makes it easier for us to share the pleasure of her acquaintance more widely.

Great story, interview, and pictures! Thank you for all of your work, Beth, and thank you for sharing, Owen.

Thank you so much for the kind compliment, Charlie!

So thorough. Written in a way novice gorgonian lovers can take in the depth (ha) of information.

Thank you kindly, Joëlle. We appreciate the pun, too!

What are some unique strategies or experiences that Westmont College students have utilized to co-author scientific papers with faculty members, and how can these approaches be replicated by students in other institutions?

Great question about student coauthors. I've reached out to Beth Horvath to see if she has any thoughts for you.