Thanks for the Memory: A Not-So-Brief History of the Transformed Halls

If the Museum was part of your childhood, chances are you’ve enshrined our halls in your memory. You may have wondered (or even worried about) whether it was possible to update the halls without losing the history that makes them so special. We wondered about that ourselves. Actually, we obsessed over it. When you visit, we think you’ll be pleasantly surprised to discover that while much has changed, the historic character remains intact. We were able to honor our history because we understand and value it.

As an institution, we rely heavily on Librarian Terri Sheridan to preserve our memories. “Librarian?” you might be thinking, “What librarian?” Such a title implies the existence of a library, and relatively few visitors discover ours. Like Platform 9 ¾, it’s hiding right under your nose, but there’s no trick to entering; the magic is all inside.

Inspired by Museum patron Max Fleischmann’s personal library, the high-ceilinged space is ringed by the watchful eyes of the African game animals Fleischmann collected himself. He’s up there, too, but only in portrait form, gazing down from above a mantelpiece framed by massive elephant tusks. Heavy mission-style furnishings contribute to the old-school atmosphere, as do the evocative odors of books, wood, and leather. Every detail encourages you to sit down and crack open a book, and all visitors who discover this atmospheric chapel of scientific literacy are welcome to do just that. The books range from a 16th-century German-language tome on medicinal plants (tucked away in the rare book room) to modern children’s books, and the catalog is searchable from the Central Coast Museum Consortium’s online portal.

Not only does Sheridan keep the library organized and accessible, she oversees the SBMNH Archive: a large collection of documents and ephemera connected to our history and the work of affiliated researchers. If you sit down for story time with her, you’re guaranteed to learn something interesting about the Museum, like the connection between our exhibit halls and one of America’s greatest panoramic painters, Thomas Moran.

Part 1: The Early Bird Years

Though his works are beautiful, Moran wasn’t only interested in painting pretty pictures. Before photography became more accessible, panoramic paintings of unspoiled wilderness in the American West functioned like activist photojournalism. Works like Moran’s 1872 Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone influenced political decision-makers to set aside land for preservation. In the early 1900s, this style of painting was repurposed to create backdrops for museum dioramas, which cultivated the love of nature and an interest in conservation among the general public. To create realistic, seamless vistas, artists painted on curved walls and used forced perspective to fool the eye.

Thomas Moran’s 1872 painting Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Moran lived in Santa Barbara at the end of his life, and was a Resident Artist at the Santa Barbara School of the Arts (SBSA). He inspired many painters working and studying here. The SBSA is the link in the chain tying Moran—a true American icon—to the artists who painted our earliest dioramas. SBSA founder Fernand Lungren had strong ties to our Museum, even from its early years as the Museum of Comparative Oology (the study of eggs and nests). “The School of the Arts sort of had fingers out into all of the cultural institutions that were happening in Santa Barbara at that time,” Sheridan explains. And during the 1920s, “as far as museums, we were the only game in town. So there was a cross-pollination of talent. Many of our artists in residence were also teachers at the School of the Arts.”

Because of our roots in oology, our first exhibits were strictly bird-centric. One of our early halls housed cupboards of nest and egg specimens which were open to the public to explore. Was this like a 1920s version of the Curiosity Lab? One might speculate that it was quieter. This free-for-all came to an end in the mid-twenties, when professional museum consultant Paul Rea advised us to guard our specimens with greater care.

In the space now occupied by Gem & Minerals Hall, Little Bird Hall housed bird group dioramas from 1922 to about 1960. Lungren used his influence in the local art world to mobilize SBSA colleagues to paint in Little Bird Hall. He himself painted a grand, 21-foot-long Mojave Desert scene for the Desert Bird Group diorama in 1925. It’s one of few early exhibits of which we have a photograph.

1923 photo of Lungren’s Mojave Desert painting in Little Bird Hall. Bird ID is harder in black and white, but some shapes—like the Greater Roadrunner—are unmistakable.

Howard Russell Butler—a painter distinguished for his unusual skill at capturing fleeting moments—painted a seascape behind Little Bird Hall’s Shorebird Group. Butler studied under Frederick Church (another luminary of the Hudson River School, like Thomas Moran) and also painted for the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Today, astronomy fans know the Hayden as the home institution of Neil deGrasse Tyson, but for many years it also housed Butler’s extraordinary paintings of solar eclipses. In 1923, he painted a total eclipse of the sun he’d observed from a vantage point near Santa Barbara, and that became the central piece in an eclipse triptych long installed above the Hayden’s doors. You can learn more about Butler’s remarkable artistry and unusual techniques at the Princeton University Art Museum website, which honored him with an online exhibition coinciding with last year’s solar eclipse. To speculate about the background for our shorebirds (of which no photograph has been found), scroll down on this page to see three paintings from a Santa Barbara beach painted by Butler as the afternoon light waned.

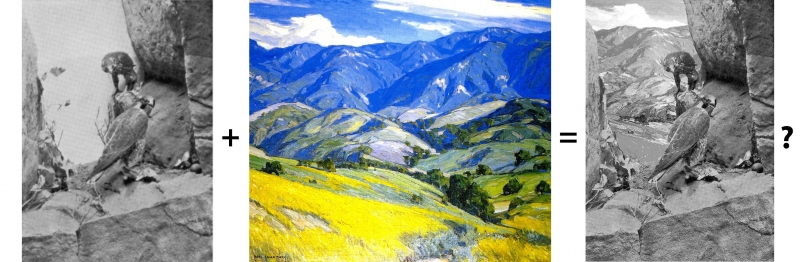

Carl Oscar Borg was another SBSA teacher drafted to paint for the Museum. Borg was a Swedish transplant to the Los Angeles art scene, and worked as an art director on silent film classics like The Black Pirate (1926) starring Douglas Fairbanks. Again, we have no photo of his painting for the Duck Hawk Group (Peregrine Falcons are also known as Duck Hawks), but we do have a photo of the diorama, as well as an image of his 1924 painting of the Santa Ynez Mountains.

The Peregrine Falcon in the foreground remains on display in Bird Hall today, still tenaciously clutching a Mourning Dove.

Another painter of early bird exhibits was Cadwallader Washburn (expectant parents in search of unique names, take note), who studied at MIT, the Art Students League of New York, and the Académie Julian in Paris. Washburn’s hearing was severely impaired, but this doesn’t seem to have curtailed his exploits throughout a remarkable life. A member of our Board of Trustees in the early twenties, he went on a collecting trip to the Marquesas Islands with the Museum’s support, “spending extended time with a cannibalistic tribe whom he taught to sign so they could all communicate,” says Sheridan. (Read more in “The Incredible Story of Cadwallader Washburn,” disability rights activist Frank G. Bowe, Jr.’s 1970 article in The Deaf American, vol. 23, no.3. It may not be in your personal library, but it’s available in ours!) His painting for the Marsh Bird Group was set in Santa Barbara’s Hope Ranch neighborhood.

Part 2: Beyond Birds

In the mid-1920s, the goals of the Museum’s Board of Trustees expanded beyond birds, and founder W.L. Dawson was pushed out of the picture. It had never been Dawson’s intention to start a museum: he had moved to California to write a book, Birds of California (subsequent to his Birds of Ohio and Birds of Washington). His massive private collections had only become a museum at his wife’s urging. In the early twenties, while Dawson fixated on finishing Birds of California, trustees Caroline and Mary Hazard steered the Museum out of the nest. They were assisted by Cate School teacher Ralph Hoffmann, a birder and botanist who mobilized community support for the Museum’s expansion and succeeded Dawson as director. It’s a measure of Hoffmann’s love of nature that he worked as director for four years on a volunteer basis, all while continuing to teach at Cate. This entailed driving back and forth from Carpinteria on primitive roads in an era predating today’s comfortable car upholstery. Would you do that? No? Maybe it’s time to consider a new workplace.

Soon after we expanded our scope, we accepted Fernand Lungren’s collection of Native American artifacts, and we built our original Marine Hall…but those are stories for other blog posts, as today we confine ourselves to the historical fun facts of the three recently transformed halls. The creation of Mammal Hall was bankrolled by the aforementioned nature-loving, big-game-hunting, yacht-sailing yeast tycoon Max Fleischmann, whose impact on the Museum extended well beyond those exhibits. His generosity allowed the Museum to really stretch its wings by funding the expansion of the campus, the construction of seven buildings, and the growth of our scientific collections.

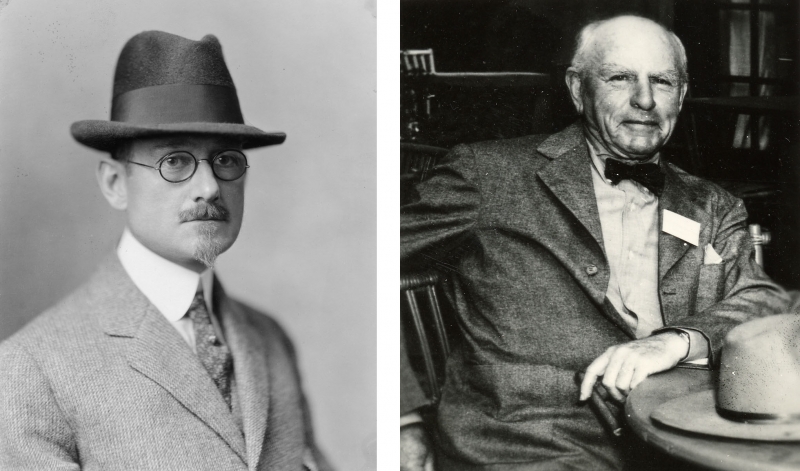

Two who made a big impact: bird lover W.L. Dawson (left) and yeast magnate Max Fleischmann

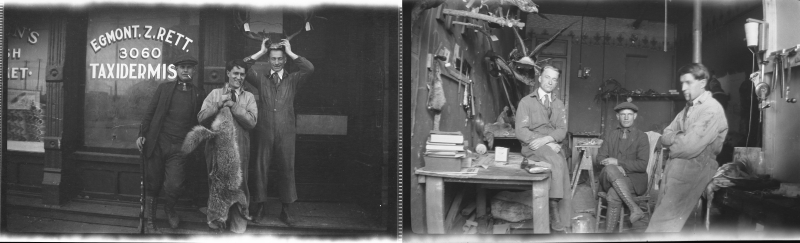

Fleischmann funded bounties that allowed the Museum to acquire large mammal specimens. The job of preparing these fell to a pair of brothers who were renowned taxidermists: Egmont Rett (known simply as Rett) and Arthur “Swede” Rett. Their expert work brought beautiful painted landscapes to life, as they prepared all of the mammals in Mammal Hall (except for the Grizzly Bear, which came from James L. Clark Studios in New York). The attentive Mule Deer parents, the playful Mountain Lions under their mother’s watchful eye, the majestic Tule Elk bull, the Black Bear cub inspecting his hind paw…all are masterpieces of naturalistic taxidermy.

The Rett brothers and an unknown colleague at work in the early 1920s

Because a well-mounted piece of taxidermy can last for many decades if properly cared for, these specimens are our Museum family heirlooms, and it’s been an honor for our curators of Vertebrate Zoology and Exhibits Department staff to steward them through the ages. As Director of Exhibits Frank Hein put it in his recent piece for SBnature Journal, “We consider Mammal Hall to be something of a chapel to the natural history of our region. Its look and feel is, in a real sense, sacred. We approached the design process with that thought in mind. We took out all the items that had been added over time, to bring the hall back to what its creators intended.”

California Sea Lion diorama in Mammal Hall, 1928 and 2018

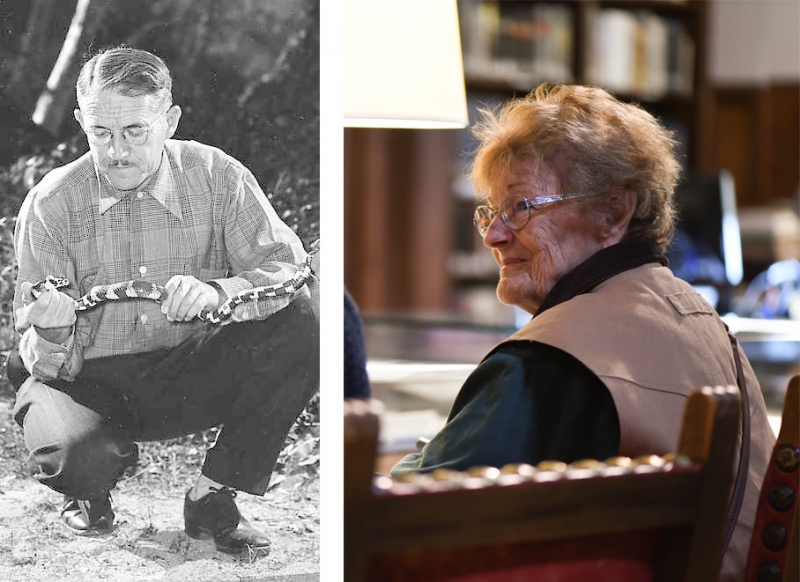

New panels by Gallagher & Associates and Cinnabar honored the old-fashioned feel of the hall, while bringing the interpretation up to date with modern science and conservation efforts. Dixon Studios—diorama specialists who enhanced the scenes in all three transformed halls—paid special attention to our mammals, painstakingly restoring them to their original glory in a fascinating process. In April 2018, Egmont Rett’s daughter Crystal revisited Mammal Hall, inspecting changes and bringing joy to Hein with her words of approval: “Dad would have loved this.”

Egmont Rett c. 1950, his daughter Crystal Gordon in the Museum Library in 2018

Soon after Crystal’s visit, taxidermist Allis Markham’s Los Angeles-based shop Prey Taxidermy provided more than 50 new mounts to supplement the Rett pieces. The largest new specimen is a female California Sea Lion, prepared with help from Markham’s mentor Tim Bovard, staff taxidermist at Natural History Museum of Los Angeles for over 30 years.

Tim Bovard and Allis Markham contemplate installation of the female California Sea Lion

In addition to the artistry of the taxidermy, Mammal Hall has many other charms. Its fine-carpentry architecture of dark wood sets off the scenes beautifully, creating the classic diorama effect of “windows into nature,” as Markham puts it. It has charismatic megafauna going for it, as well as the fact that its target audience is a subset of mammals, the human mammal (a concept the new interpretation discusses, with refreshing humor and thoughtfulness). It also has beautiful background paintings, some of which are nearly as old as the lost backgrounds of Little Bird Hall.

Fernand Lungren painted the Death Valley scene behind our Bighorn Sheep. The locale (the view from Dante’s Peak) was close to his heart. As art historian Jane Dini wrote in The Art of Fernand Lungren (a catalogue accompanying the exhibit of the same name at UCSB’s Art, Design & Architecture Museum):

Lungren was enchanted with the entire Southwest, but the desert he would return to paint again and again was Death Valley. For over 20 years, the vista from Dante's View, a vantage point high above the desert floor, would become his signature view. In Lungren's striking panorama Death Valley: Dante's View..., he juxtaposed the impressive peaks with the low desert floor streaked with salt rivers. Here was the serene beauty of the desert coupled with the drama of geological creation. In 1911, from Dante's View, the artist wrote to his 'Beatrice': 'I think of you constantly, my sweet wife, and at night I look at Sirius, the bright star near the constellation of Orion, and tell myself that you too are looking at it.' From the romantic to the awesome, Death Valley inspired some of Lungren's most dramatic compositions.

So the next time you look at those sheep, let it be with a tear in your eye, or the words “hubba hubba” on your lips.

Lungren’s successor at the SBSA was Renaissance man Belmore Browne. In addition to painting, he scaled mountains and collected and prepared specimens. He painted the Grizzly Bear background, the Antelope Buttes mural in the Pronghorn Antelope diorama, and the Harbor Seal and jackrabbit backgrounds. The Oso Canyon scene behind the bear is probably the most impressive. In it, Browne’s use of startlingly bright blues to render shadows, and the broad, dry, squared-off brushstrokes that mimic coarse, blocky natural textures is reminiscent of his 1926 painting The Chief’s Canoe in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Browne was the final president of the SBSA. It closed in 1933, a victim of the Great Depression.

Some of the Mammal Hall backgrounds were painted by our multitalented taxidermists, Egmont Rett and Norton Stuart. Stuart’s romantic mountainscape behind the Black Bears remains intact, but this year the landscape he painted for the Mule Deer diorama was replaced, as it no longer appeared as intended. Whether this was due to chemical instability in the paint or an inexpert touch-up job isn’t known, but the replacement artwork by professional muralist Jan Vriesen injects more lifelike details while keeping the old sense of space.

Vriesen also painted the background for the new triptych diorama at the north end of Mammal Hall, a playful Mission Creek scene showing interacting mammal families. Raccoons fish in the water, skunks and opossums are on parade, and a mother coyote brings a meal home to her pups in the den below. The young coyotes—textured ceramics by Dixon Studios—are adorable, touchable, and strategically placed at kid height.

Dixon Studios diorama specialists are shown where they belong: in the diorama representing mammals found on our Mission Creek campus.

This is a homecoming for coyotes, which were banished from Mammal Hall by logistics when the space was expanded to make way for Bird Hall in the early sixties. The old coyote diorama stood right where the doorway to Bird Hall was destined to be, so the pack got the push.

The original coyote diorama was a desert scene painted in 1927 by Elizabeth Jordan, later repainted by the versatile painter Lilia Tuckerman (who also painted the Kern County scene behind our Tule Elk couple). Tuckerman's version of the coyote diorama depicted the Gaviota Pass before the construction of Highway 101. Jordan’s atmospheric background for the Gray Wolf diorama remains in place today, giving a suggestion of what the lost coyote diorama may have been like. In addition to being an art student at the Santa Barbara State Teachers College (predecessor to UCSB), Jordan worked as a secretary at the Museum. She was neither the first nor the last SBMNH employee to find herself doing something that wasn’t on her job description, and like many of the other painters in Mammal Hall, her work was likely a labor of love, not a money-making proposition. As Development Officer Melissa Baffa put it recently, the Museum has a “culture of philanthropy” in which everyone contributes according to their talents, not just their titles.

As Sheridan says, artists donated their time because “we were, even then, sort of a beloved little cultural [institution] that was growing, and they believed in what we were doing.” Some of these early painters may have received stipends, but Sheridan reports, “I’ve found very little thus far that tells me how much the artists were being paid. …I always say thus far because this place uncovers things as you go along.” Case in point: the microscopic herd discovered by 1990s restorationists in the painting within the Pronghorn Antelope diorama. Why they were covered up remains a mystery, but today they’re visible, and give our Pronghorn Antelope pair something to look at. See if you spot them on your next visit!

Part 3: A Strong Legacy

If there’s a single person whose enduring paintings stand out in our halls, it’s Ray Strong. A colleague of Maynard Dixon, friend of Ansel Adams, and an accomplished artist in his own right, Strong bid for the project of painting all of the scenes for Bird Habitat Hall, at a price of about $1,000 per painting. This may seem like a steep increase from the pro bono days, but today we value Strong’s large-scale landscapes far beyond that price. In 1960, the Museum hired him as an artist in residence, and he settled down to several years of work. Strong’s murals benefit as much from his knowledge of regional landscapes as from his technical skill as a painter; they capture the shapes, light, and relationships of elements in real places he visited, natural treasures beloved to locals.

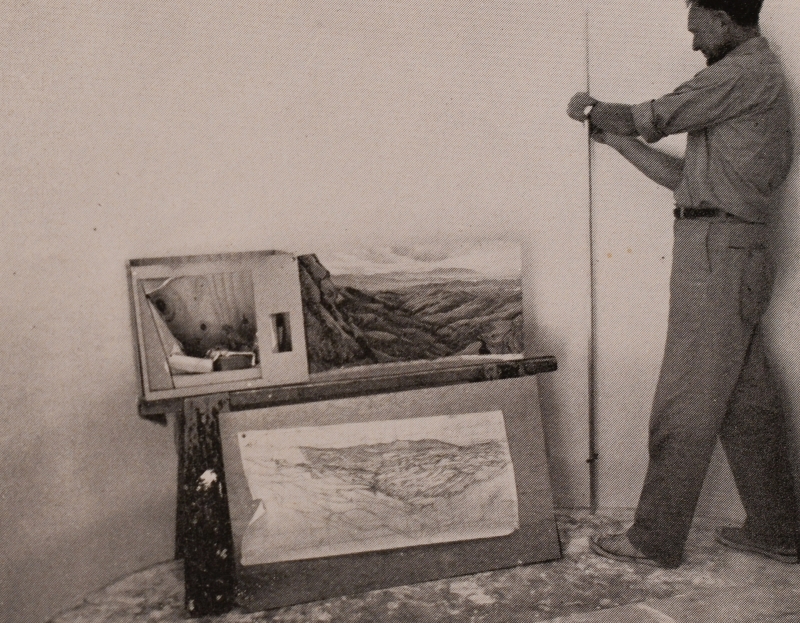

According to a Santa Barbara News-Press article published c. 1965 (the undated clipping is taped into one of Strong’s scrapbooks in the Museum Archive) Strong was an old hand at dioramas. He first painted backgrounds for the U.S. Forest Service’s Civilian Conservation Corps exhibits in the San Diego Exposition (probably the California Pacific International Exposition of 1935-1936), and went on to paint more diorama murals for the Forest Service at museums and interpretive centers. In 1939, he painted a large prehistoric scene for the Golden Gate International Exposition, where he met Vertress “Van” Vander Hoof (later the director of SBMNH). Decades later, Van recruited Strong to paint for us.

Dioramas present special challenges to the artist, as the image above hints. Strong is pictured preparing to work in the Golden Eagle diorama with his sketch, a roughed-out oil painting, and a photo modeling the placement of the specimen. Although the aperture through which the painting will be seen is fairly square, the curved walls present a wider surface area, which has to accommodate the inherent distortion of perspective caused by these curves. When painted by a master such as Strong, a panorama looks and feels natural and right.

Then there’s the difficulty of blending a painting with foreground elements, and finally, the challenge of lighting. Typewritten notes from one of Strong’s scrapbooks reveal the interplay between lighting and the artist’s work: the Goleta Beach shorebird diorama couldn’t have ordinary beach sand underfoot, because it took on a lifeless hue beneath the overhead fluorescent lights then in use. Instead, sands of different colors were sourced from Monterey, the San Marcos Pass, and the outskirts of Santa Barbara to warm the palette. Lighting dioramas is still difficult; it’s hard to mimic natural light in confined, artificial conditions. But the transformed dioramas have made huge strides with a new lighting system that allows exhibits staff to custom-tune the atmosphere and bring paintings and dioramas to life in a new way.

Strong made his contribution during a tumultuous time for the Museum. In 1962, a fire in the collections—caused by a faulty electrical plug—tragically destroyed records, damaged specimens, and consumed many of the taxidermy mounts awaiting transfer from Little Bird Hall to the new Bird Hall. A year after suffering these losses to our collections, we lost our greatest preparator, Egmont Rett (of a broken heart, said his wife).

With the completion of Bird Habitat Hall stalled by the need for new specimens, the Museum had Strong do “some other little projects here and there,” says Sheridan. This included work in the upper level of Santa Barbara Gallery (then known as the Hale-Harvey Botany Hall in recognition of Jeanne Hollister Hale and Katherine Harvey).

Hall of Flowers c. 1930, Santa Barbara Gallery 2018

That exhibit space started life as a plant hall bankrolled by Max Fleischmann, with flower cuttings on display courtesy of the local chapter of the Little Gardens Club. In 1960, Artist-in-Residence David Hagerbaumer—a specialist in sporting scenes—painted the mountain meadow mural at the south end. Strong repainted it, possibly to match his own work elsewhere, or to blend the mural with new items in the foreground.

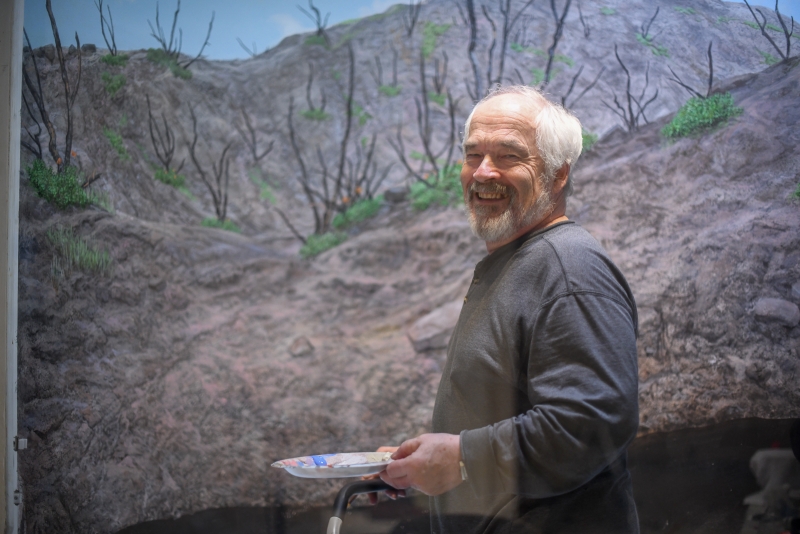

In the early 1990s, Artist-in-Residence Richard Schloss—locally known as a plein air master—gave that mural another working over, and painted backgrounds for the other dioramas in the space, which took on the name of Cartwright Interactions Hall. The focus shifted from botany to interspecies interactions within habitats, a theme continued by the space’s latest incarnation as Santa Barbara Gallery. Today, the dioramas have been enhanced with new taxidermy and new cast and modeled specimens, and the pine tree growing from the junction of two habitat scenes is a nice nod to the hall’s botanical roots. The old chaparral burn cycle diorama—formerly a vitrine which blocked the center of the room—has been treated to a niche in the wall and a background by Jan Vriesen. He researched this mural of chaparral plants recovering from a fire by taking local field trips with Exhibits Department staff and curators.

Jan Vriesen at work in the chaparral burn cycle diorama

Curators work closely with our exhibit design team to ensure that the web of life is portrayed with scientific accuracy. Curator of Vertebrate Zoology Krista Fahy took a very hands-on approach to the recent arrangement of eggs and nests in Bird Habitat Hall. In the case of our entomological diversity displays—which contain hundreds of carefully pinned specimens—the work took on heroic proportions, albeit at a bug’s scale. The 1991 display was constructed by a dedicated team including current Curator of Malacology Paul Valentich-Scott. Today’s insect and arachnid diversity case was assembled in large part by Curator of Entomology Matthew Gimmel and Senior Exhibits Manager Debra Darlington. Matt and Debra have also painstakingly added many new insect and arachnid specimens to the dioramas throughout the Santa Barbara Gallery.

Schlinger Foundation Chair and Curator of Entomology Matthew Gimmel embarks on an epic quest to fill the diversity case

However, it’s the addition of humans to these transformed halls that really brings our exhibits up to speed with modern science. We don’t mean the hard-working humans who enhanced our dioramas during the months the halls were closed. We’re talking about the new approach in the interpretive panels inviting visitors to remember that humans are part of nature, too. This means encouraging people to consider the roles we’ve played to threaten and protect the species we share the planet with. Our transformed exhibits are up-to-date with what science tells us about biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, and climate change.

We all share the natural world, and when we disturb nature’s balance, we damage the very systems that support us. Carl Sagan—like the early atomic scientists—saw very clearly that our technological capacity can do great harm. It can outpace our foresight and restraint if we allow it. The good news is that we do clearly understand the need to keep our ecosystems healthy and functioning for the good of wild things, wild places, and ourselves. Our challenge is to face the urgent need to put that knowledge to direct use, now. The Museum & Sea Center will always serve as trustworthy sources of scientific information about the natural history—and the natural future—of our region. Sound information is the foundation for informed decision-making and action. Together we can meet the challenges that face our region and our planet.

We like to think that we’ve come a long way from the mid-sixties, when a scene of a Cooper’s Hawk swooping down towards a covey of California Quail was deconstructed because the implied violence of predator-prey relations aroused controversy. One of the overarching goals behind our ongoing transformation is to illuminate rather than conceal interspecies interactions, including human impacts on the natural world of which we are a part. In that way, the history of the halls is a microcosm of the interdependency they illustrate: it takes a whole ecosystem of exhibit designers, artists, scientists, coordinators, craftspeople, and donors to create the exhibits that inspire, delight, and inform.

Exhibits Department staff in the mountain meadow diorama, left to right: Exhibits Coordinator Francisco Lopez, Director of Exhibits Frank Hein, Exhibits Administrative Assistant Florine de With, Senior Exhibits Manager Debra Darlington

0 Comments

Post a Comment