Museum Mysteries: The Disembodied Albatross

Why does Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology have a severed albatross head in its collection? That wasn’t one of our sleuth’s original research questions, but he answered it all the same. SBMNH Curator of Vertebrate Zoology Paul Collins encountered the surreal specimen while researching his book-in-development on the birds of the Channel Islands. It’s not the only mystery he’s solved over the course of that research, but it may be one of the strangest.

For the past forty years, Collins has compiled information about Channel Islands birds from specimens and field notes at institutions around the world. His sources stretch from 1843 to the present day, and include records of nearly 10,000 museum specimens and more than 150,000 observations of birds on the eight islands. The last book to cover the birds of all the islands was a slim volume published in 1917, so Collins’s book will fill a big gap in the field. Physically, the observation records fill a stack of binders 24 inches tall. In bird terms, that’s about the height of a Great Egret, those tall white birds you see in the wetlands around UCSB and the fallow fields of Goleta.

Collins with the handwritten database of bird observations, Great Egret for scale

Collins started this project in the mid-1970s, before the advent of any of the digital technology and online resources we now take for granted. Ponder for just a moment precisely how—in an era before personal computers and easily searchable web catalogs—you would find out who had Channel Islands specimens or field notes. Ask every museum if they have anything from the islands, and you rely too heavily on curatorial memory, which can’t reasonably index the scope of large collections. Ask every museum about every bird conceivably found on the islands, and you’ll be dismissed as a time-waster. So Collins meticulously followed the paper trails, starting by visiting museums along the West Coast, where island specimens were closer to home and easier to find. He scoured Joseph Grimmell’s 1938 Bibliography of California Ornithology for references to the islands, which led him to papers and books that directed him to collections. He researched the lives of collectors and expedition leaders to see where their collections ended up.

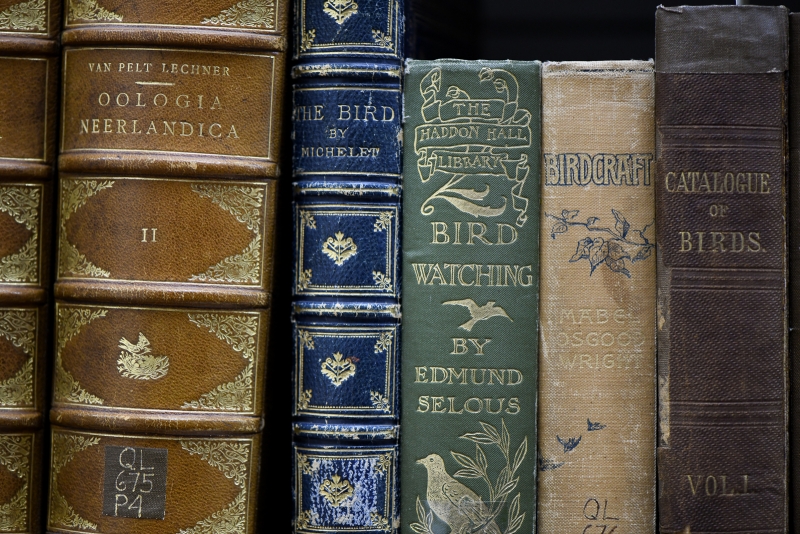

His trip farthest afield—to the British Museum of Natural History (BMNH)—started close to home, in the rare book room of the SBMNH library. There, Collins consulted the BMNH’s turn-of-the-century publication Catalogue of Birds, which cataloged all their bird specimens. Because the book lists a place of origin for each of these specimens, Collins was able to locate a series of birds collected from the Channel Islands in the mid-to-late 1800s. He visited the BMNH’s bird collection in Tring (a town outside London) to examine these specimens, and to look for additional island birds that might have been collected after the publication of Catalogue of Birds. He checked the collection for some of the more common island endemics. Taking down the catalog numbers of these specimens, Collins looked them up in the collection’s historic handwritten catalog ledger, to see if other Channel Island specimens entered the collection around the same time. A catalog ledger is a big register in which a curator logs additions to a collection. Specimens, like birds, flock together: find one specimen collected from the Channel Islands in that register, and you’ll see above and below it the list of other specimens acquired at the same time, from the same collecting expedition. The rest of the haul could include rarer birds, as well as field notes and other documents associated with the trip.

First volume of BMNH’s Catalogue of Birds, in context with other tomes in our rare book room

A published note in the ornithological journal Condor unlocked the mystery of the albatross head at Harvard. During the 1909 expedition of private collector Clarence Brockman Linton to San Nicolas Island, the head was an after-dinner leftover. Linton’s cook picked up the Laysan Albatross on the beach, and “by the time [Linton] got back to camp, the cook had carved it up and had it in the pot.” Only the head escaped the cook’s clutches, which is how it was salvaged by Linton and wound up flying solo at Harvard.

This incident of collecting as an afterthought isn’t all that surprising. Many of the animal specimens acquired by museums in these early years came from expeditions with broader aims. Bird collecting was totally incidental to the goals of geographers and geologists interested in defining borders and surveying resources. Even ornithologists sometimes did their bird collecting on the fly, working more generally as naturalists. In 1863, bird specialist James Graham Cooper was collecting shells on a boat off the shore of San Nicolas, using an apparatus for scooping up animals living in the mud on the ocean floor. A Short-tailed Albatross (now one of the rarest bird species in California) wandered nearby, and he shot it.

Collins and Yale Peabody Museum Vertebrate Zoology Collections Manager Kristof Zyskowski, examining one of Cooper’s albatross specimens at the Peabody in 2007. Photo courtesy Paul Collins.

Collins puts some of these early collectors in context: “They were naturalists. They might have had a focus on a particular animal group, but in general they were looking at all natural history. They might be collecting plants, they might be collecting herps [reptiles and amphibians], they might be trapping mammals and shooting birds. They were collecting all of this stuff, because there wasn’t a whole lot known.” Scientists continue to describe new species and learn more about known ones, but at that time the field was full of low-hanging fruit, ripe for picking by any enthusiast.

The downside of this target-rich environment was occasional overcollecting: collectors—private and institutional—collected more individuals than they really needed, contributing to population decline in some species, particularly those with small ranges. Additionally, the primitive state of information technology made it hard for scientists to share information, so specimens languished in museum drawers without making a contribution to our knowledge. In his Channel Islands bird search, Collins came across two Island Fox specimens at the British Museum of Natural History, collected ten years before the species was finally described by scientists in the United States. Collins explains that the foxes probably waited in limbo at the BMNH because curators “didn’t know what they had, and there wasn’t an easy way for individuals working in a particular country to know what other institutions had in their collections if you didn’t travel there.”

A forlorn Island Fox specimen at the BMNH that missed its chance to become the basis of a new species description. Photo courtesy Paul Collins.

Since then, technology has revolutionized museum work. Though much of that low-hanging fruit has been picked, it’s now arguably easier for scientists to describe new species, because of the speed with which they can share information and collaborate. Globally, museum professionals are engaged in a vast project of digitizing and sharing museum collections data with colleagues and the general public through institutional websites, professional networks, and massive research portals like the NSF-funded iDigBio.

Technology hasn’t only changed how we share specimen data. As new techniques for analysis are developed, it periodically allows us to extract more information from existing specimens. George Davidson, who visited San Miguel Island in 1871 for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, would never have dreamed that the skins of the Bald Eagles he collected there would show—more than 100 years later—what those birds ate. Collins tracked down those birds—now housed at the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences—and worked with Dr. Seth Newsome of the University of New Mexico to obtain stable isotopes from samples of their feathers. Stable isotope analysis is a remarkable technique based on the fact that you really are what you eat: isotopes that are abundant in an animal’s food sources will later be abundant in its body. Collins also analyzed the bones and other detritus present in historic Bald Eagle nests on the islands, which provided a sort of CSI window onto their meals of the past. Together these analyses were instrumental in proving that the Bald Eagles historically present on the Channel Islands ate mostly fish, and not Island Foxes. Who cares what Bald Eagles ate in the 1800s? Conservation biologists, land managers, and anyone who’s enjoyed meeting an Island Fox…which increasingly means anyone who’s visited the Channel Islands.

Island Fox, Santa Cruz Island near Prisoners Harbor

Many locals know the bare outlines of the restoration on Santa Cruz Island, but few of us know the full ecological story, or the role played by our national bird. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Channel Islands were home not only to the Island Fox (which was endemic, meaning it lived only there), but to fish-eating Bald Eagles. These birds are highly territorial, and drive other large birds of prey out of their ranges. In the mid twentieth-century, the pesticide DDT led to eggshell thinning and reproductive collapse in the Bald Eagle population. The decline of the Bald Eagles opened the large avian predator niche, but as ecologists know, niches don’t remain empty for long. Without territorial Bald Eagle bouncers to keep them away, young Golden Eagles from the mainland swooped in to fill the gap, and after DDT ban, they really had a chance to thrive.

Humans unwittingly did several other favors for the Golden Eagles. European ranchers brought game animals to the islands, including feral pigs. The pigs bred year-round, providing a steady food source for the Golden Eagles in the form of tasty piglets. The Golden Eagle population rose in response. Ranchers also brought livestock, and their grazing patterns altered the ecosystem, clearing woodland habitat and creating more grassland. This literally cleared the way for Golden Eagles to prey on Island Foxes, who now had to do more of their foraging out in the open, highly visible from above. The foxes—previously apex predators with no natural enemies—were easy targets for Golden Eagles, and their population plunged into endangered status.

Efforts to restore Santa Cruz’s natural balance involved the removal of all non-native grazing mammals, an Island Fox captive breeding program, capture and translocation of Golden Eagles to the mainland, and finally, the reintroduction of those fish-eating Bald Eagles. Bald Eagles are now resident on three of the five islands in Channel Islands National Park, doing their best to keep Golden Eagles out of their recovered territory. Correspondingly, Island Fox populations have rebounded, and last year they made it off the endangered species list. So if you see a fox, thank an eagle.

Island Fox patiently waiting for prey

As this story shows, Paul Collins’s research is already up to speed with modern technology. His task now is to do the same with his documentation, to better share the information in the Great-Egret-sized stack of binders. Fortunately, it’s already partly digitized. The National Parks Service funded the beginning of the work, which digitized all the bird specimen records and sighting records for 68 species of birds across the five islands in the national park. Now Collins is looking to the Nature Conservancy for a grant to complete digitizing the remaining bird sightings, which are all from Santa Cruz Island. Once digitized, these resources would form part of a much larger long-term digitizing and data accessibility project envisioned by the Nature Conservancy, the California Islands Biodiversity Information System (Cal-IBIS). Cal-IBIS aims at making a vast body of Channel Islands data uniformly available to researchers, and the initiative is targeted at digitizing the hard copy data of folks who are about to retire, while they can still pass on any associated institutional memories. “Data rescue” projects like this are key to ensuring the career-long efforts of researchers like Collins fulfill their potential as contributions to science.

The collective potential contribution of Cal-IBIS is monumental. The resource could include photomonitoring data, georeferenced camera trap data, historical images, geographic data about cultural resources, geographic data about rare and invasive plants, historic weather and fire data, water quality and temperature data, data about foxes, mice, snails, pinnipeds, lizards, insects, and so much more. If you want to answer big questions, you need big resources. Cal-IBIS would be a resource that could answer some very big questions about the biodiversity of the Channel Islands, and how life there has responded to changing conditions over time. It could be particularly valuable in establishing a baseline for life on the Channel Islands prior to more dramatic future changes wrought by shifting climate patterns, human interventions, and invasive species. It will also inform the future of museum collecting by illuminating gaps in the scientific record. In short, it could solve a lot of mysteries.

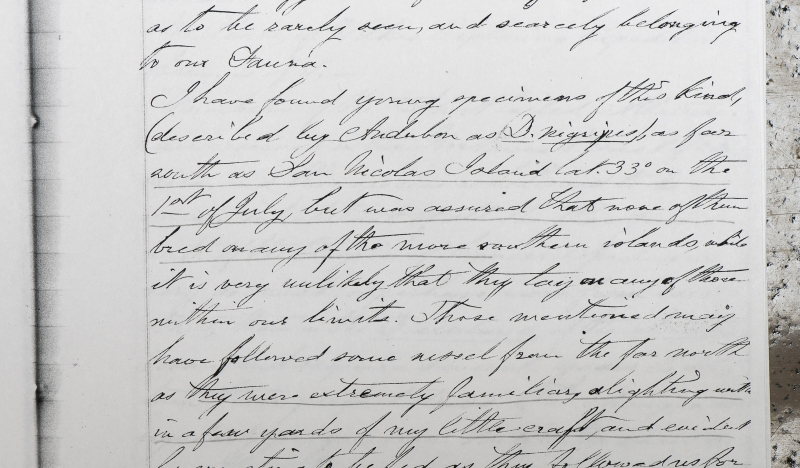

Unpublished manuscript by Cooper, describing albatross encounters at San Nicolas Island

6 Comments

Post a CommentThis is a fascinating article! The Channel Islands are a wonderful habitat.

Thanks, Pam! They sure are.

Great photos. Loved the patient hunting fox.

Thank you, Joëlle! I had to be patient to take the photo, too...but not a patient as the fox.

This is a wonderful story. It shows how valuable field notes, museum specimens and all archives are to scientific research. A paper was published in 2016 in which a tiny piece from an old SBMNH Vertebrate Zoology California Condor study skin (OS 545) provided mitochrondrial DNA. "Ancient DNA reveals substantial genetic diversity in the California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) prior to a population bottleneck".

Great article! Thank you for all those years of work Paul, what a wonderful contribution to science. Your hard work will continue to help more scientists for generations to come.